Thanks to a grant from Pollinator Partnership Canada, in January we acquired native seed to establish pollinator meadows. We now have a full season’s experience with Satinflower’s Coastal Seed Blend at a sweet spot in Kitsilano (with enough for another 100 m2). This blog explains why we prioritize native species, and shares impressions of the meadow’s progress from February to October 2024.

Why native seed, why native plants?

We’re passionate about creating habitat for native bees, and therefore prioritize native plants wherever and whenever we can. On the one hand, “native bees and native plants evolved in mutual relationships with each other over the last 100 million years”. This means that landscapes with native plants will benefit native bees. On the other hand, and taking it deeper, some of BC’s bee fauna are pollen specialists. This means they only use the pollen from specific plants for their offspring. Given their evolutionary relationships, those plants are all native. Check out Jarrod Fowler’s brilliant work on pollen specialists by clicking the image below.

For clarity, adult pollen specialist bees will consume pollen and nectar from a variety of plants, like any bee. The main difference is that they provision their offspring with pollen from a particular species or genus. So it’s actually the baby bees (i.e., larvae) who are the pollen specialists, as that’s what they consume in their early days. Noticeable features of the pollen specialists shown above are the hair and other pollen-carrying adaptations (scopa) of their bodies, which suggest they are effective pollinators.

Happily, landscapes that support specialist bees also benefit generalist species who have less restricted floral palates. Common generalists include most bumblebees, as well as honeybees (which are non-native). Even if we don’t know what bees are around, native plants are generally a good bet for wildlife. In fact, choosing native plants for landscape projects can represent a form of biological inclusivity, as these plants include the needs of specialist bees, with no harm to generalists. (Check out the Native Bee Society’s forage resources for specialist bees.)

Pollinator-friendly meadow seed blends: read the ingredients

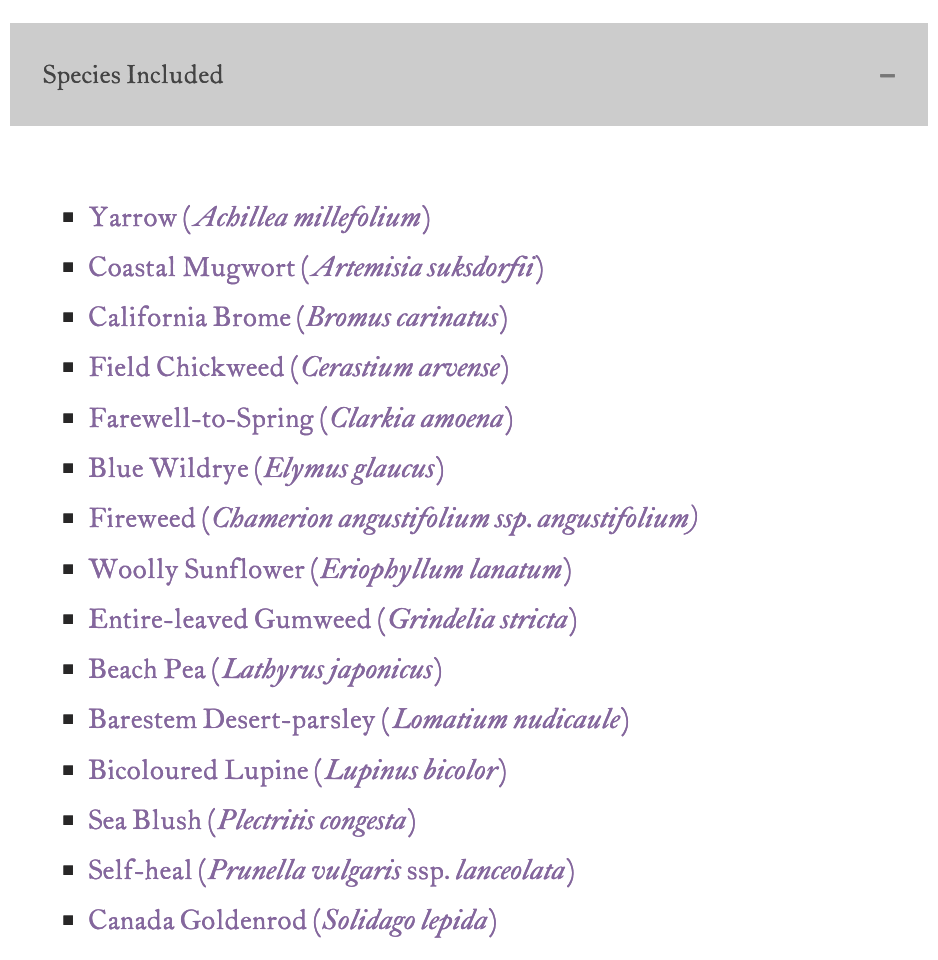

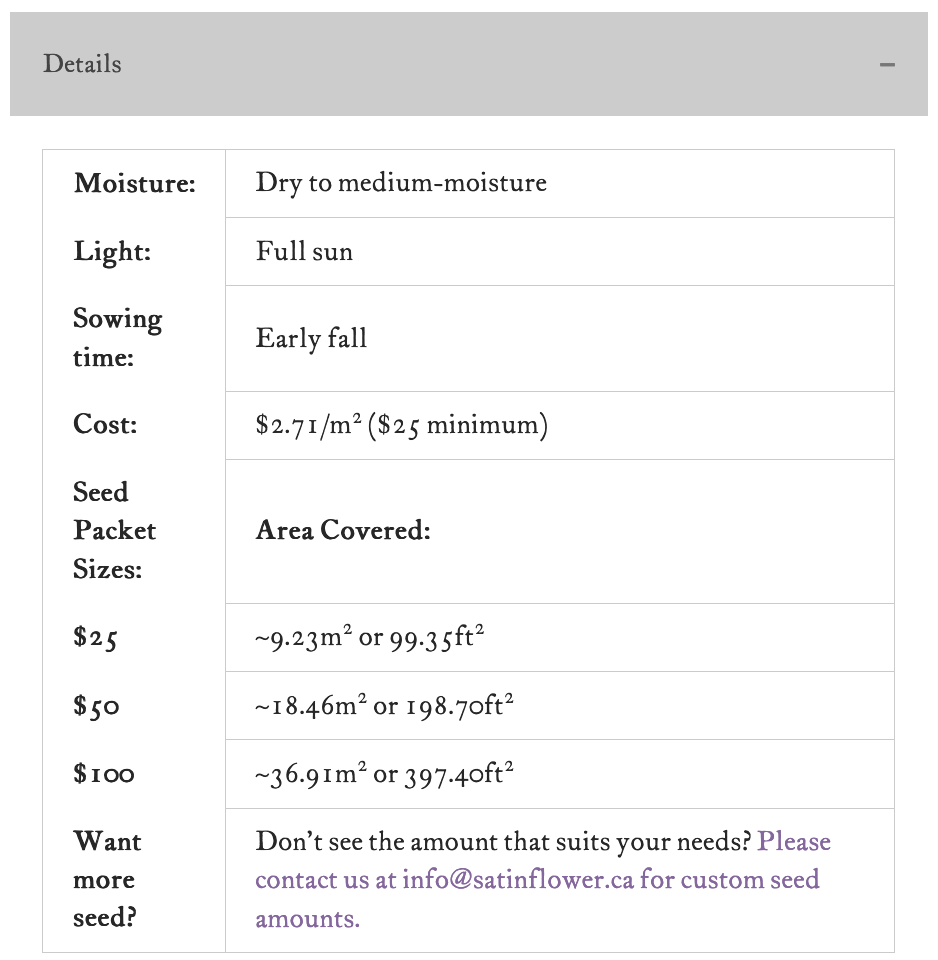

The seed blend that we’re experimenting with is the Coastal Blend by Satinflower Native Plant Nursery. The specifications are shown below, though the blend may change depending on the year. It’s an excellent mix for dry- to medium-dry sites in full sun. In our opinion, this is a nursery with integrity; the good people behind Satinflower are in it for all the right reasons. In addition to the Meadow Makers course (which is excellent), their methods, expertise and commitment to relationships are all solidly rooted in regenerative principles and reconciliation. Compared to other companies that do seed blends, Satinflower also stands apart for their fidelity to native species.

“Wait,” you may think, “don’t all pollinator-friendly seed blends comprise native plants?” While that might seem obvious, this is rarely the case in BC. For example:

- Of the 18 species featured in this Bee Garden Wildflower Blend, the majority originate from other parts of the world. Only one (Erigeron speciousus) is native to south-western BC; two are native to the southern interior (Gaillardia pulchella, Gilia capitata); one is naturalized (Eschscholzia californica).

- This Bee-Friendly Flowering Mix has only one native plant (Achillea millefolium) and 86% of the blend is non-native grasses! (How is that bee friendly?).

- This Coastal Pollinator Wildflower Mix “is designed to attract native bees, bumble bees and other beneficial insects”, yet only 5 of the 14 species are native to coastal BC.

We don’t mean to criticize those suppliers, only to raise awareness that most pollinator seed blends are low on native species. If you want native species, read the ingredients.

Pollinator Meadow at West Point Grey Road

On Feb. 6, 2024, our partners at the Vancouver Parks Board seeded the Coastal Meadow Blend onto 100 m2 of prepared soil. As you can see in the chrono-sequence below, germination was slow, but from June through July the spring annuals gave a fabulous display and the whole community started to pop! By October, only 5% bare ground was visible and the native bunchgrasses (Bromus carinatus, Deschampsia cespitosa, Festuca roemeri) and species like coastal mugwort (Artemisia suksdorfii) created nice visual accents.

Of the 16 species sown, six did not establish. Three of those (Allium cernuum, Camassia quamash, Lomatium nudicaule) require cold stratification, which is a process of essential conditions without which seeds will not germinate. In this case, the seeds of these 3 species will remain dormant unless they’re exposed to both cold and moist conditions. What this means for the meadow is that they are likely still in the seed bank and may germinate next season. Last winter was relatively warm, so our February seeding may have missed the cold temperatures.

Three other species also failed to establish (Armeria maritima, Cerastium arvense, Solidago lepida) but they do not require cold stratification. Their absence is a mystery, as Satinflower are confident the seed is viable. Fortunately, we have pre-grown pots of Armeria and Cerastium in progress! As can be expected, some non-native volunteers established, too. All are typical urban species, like Cerastium fontanum, Hypochaeris radicata, Melilotus albus, Rubus armeniacus, Trifolium spp, Plantago lanceolata, Ranunculus repens, Sonchus asper, Taraxacum officinale, etc. To pollen specialists, these plants are “wasted real estate”, so we will replace them with desirable natives.

Autumn intervention is imminent, and will include a couple of tasks. Notably, we’ll remove the undesirable volunteers and replace their footprints with pre-grown native species. Fortunately, we have 4″ pots of Cerastium arvense ready to go, as well as a number of other fantastic native perennials. Being pre-grown and planted in autumn, we hope these plants will outcompete the aggressive non-natives. By removing the volunteers, we’ll also create space for plants in the seed bank to germinate. Further to plant adjustments, the fencing will be replaced with a lighter, more organic fence. Good times ahead!

We’d love to know your thoughts (including questions), please share them in the comments below. If you happen to visit the meadow, please take a photo and share it with us! Lastly, our aim is to co-create meaningful habitat everywhere, so if you’re inspired by this vision and would like a native pollinator meadow, please get in touch.

8 thoughts on “Kits Pollinator Meadow: Season 1 Success”

Excellent piece.

Thanks, Dusty, I’m inspired by your work with seeds, meadows, solitary bees and urban habitat creation, and hope that someday I will be a vector of native seed like you!

This is amazing! Something to refer to over time 🐝

Indeed, Barb, it’s so valuable to have a site that can be observed over time. I’m so grateful for this partnership with the City, and it’s been both fun and constructive to learn-by-doing together!

Hi, it’s great to see more awareness happening around prioritizing native plants to support pollinators. Once established, how much maintenance in required to maintain a pollinator meadow such as this one?

Thank you, Ruth! To your question, maintenance for a meadow like is about twice/ year, once in late-winter or early-spring, and then once in the autumn. The specific timing of those maintenance interventions (e.g., cutting, trimming, soil disturbance) will ideally occur at periods when our insect friends are not physically vulnerable or impact critical life cycle stages.

Fantastique! What a wonderful resource.

Merci, ReGen! Let’s build a meadow on some of your projects.